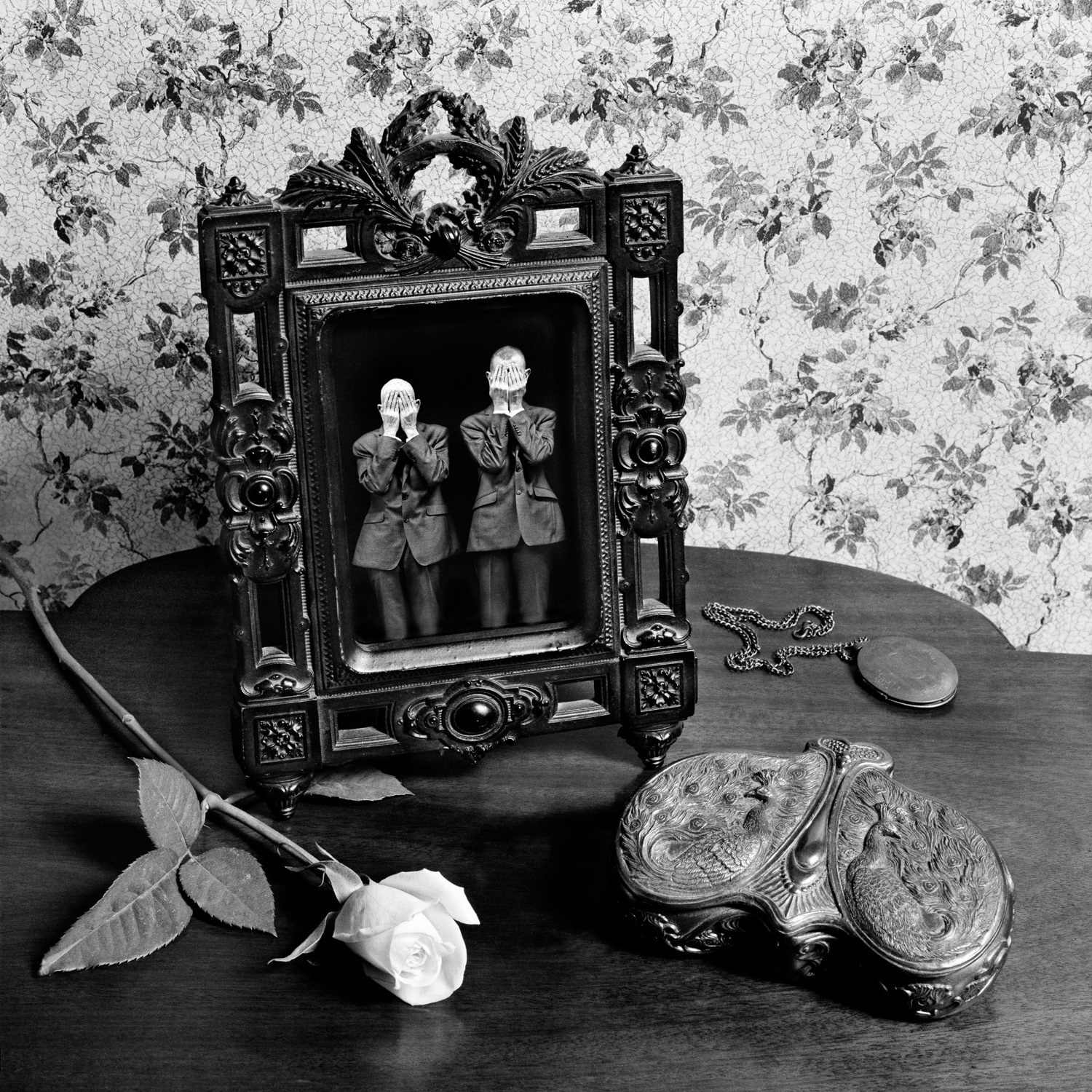

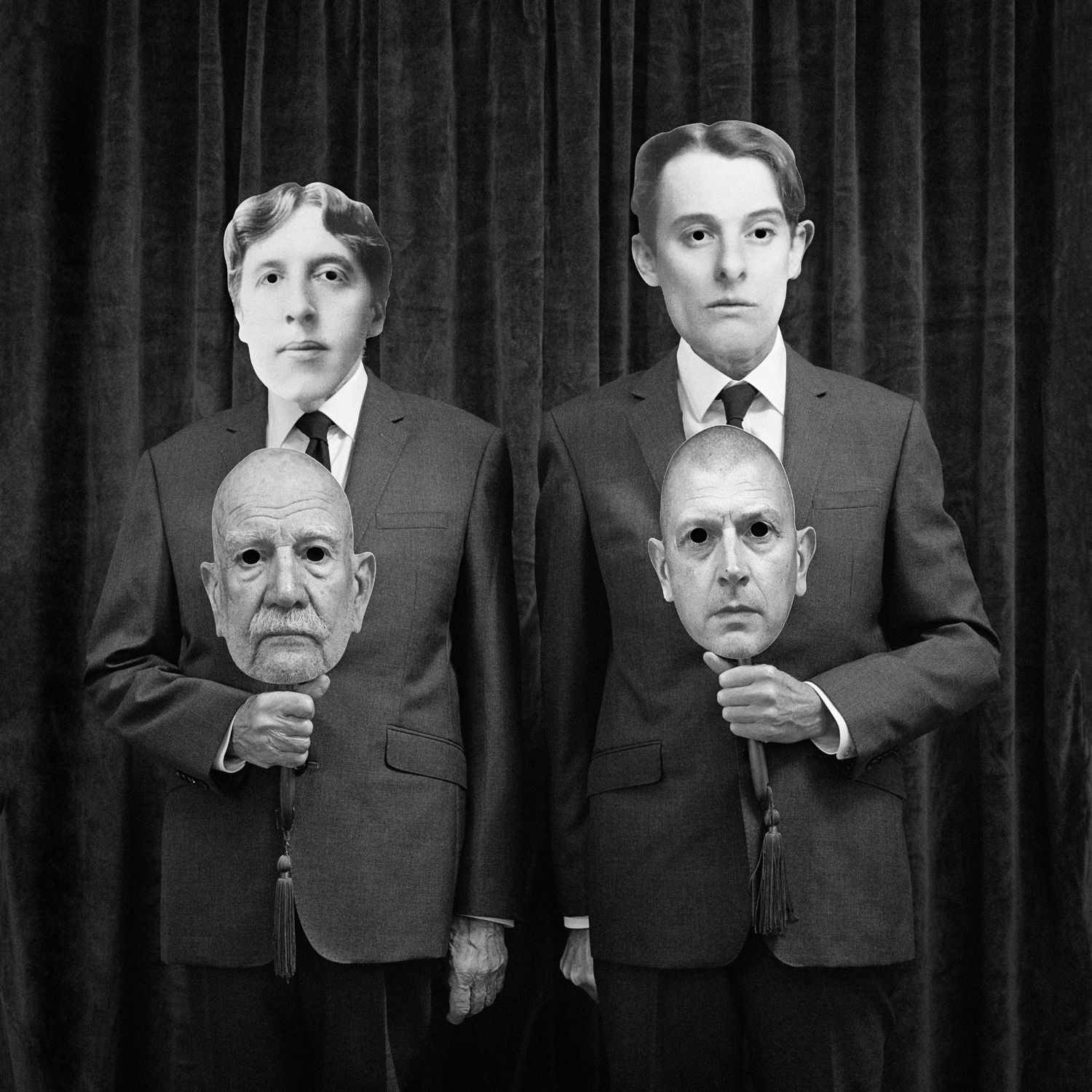

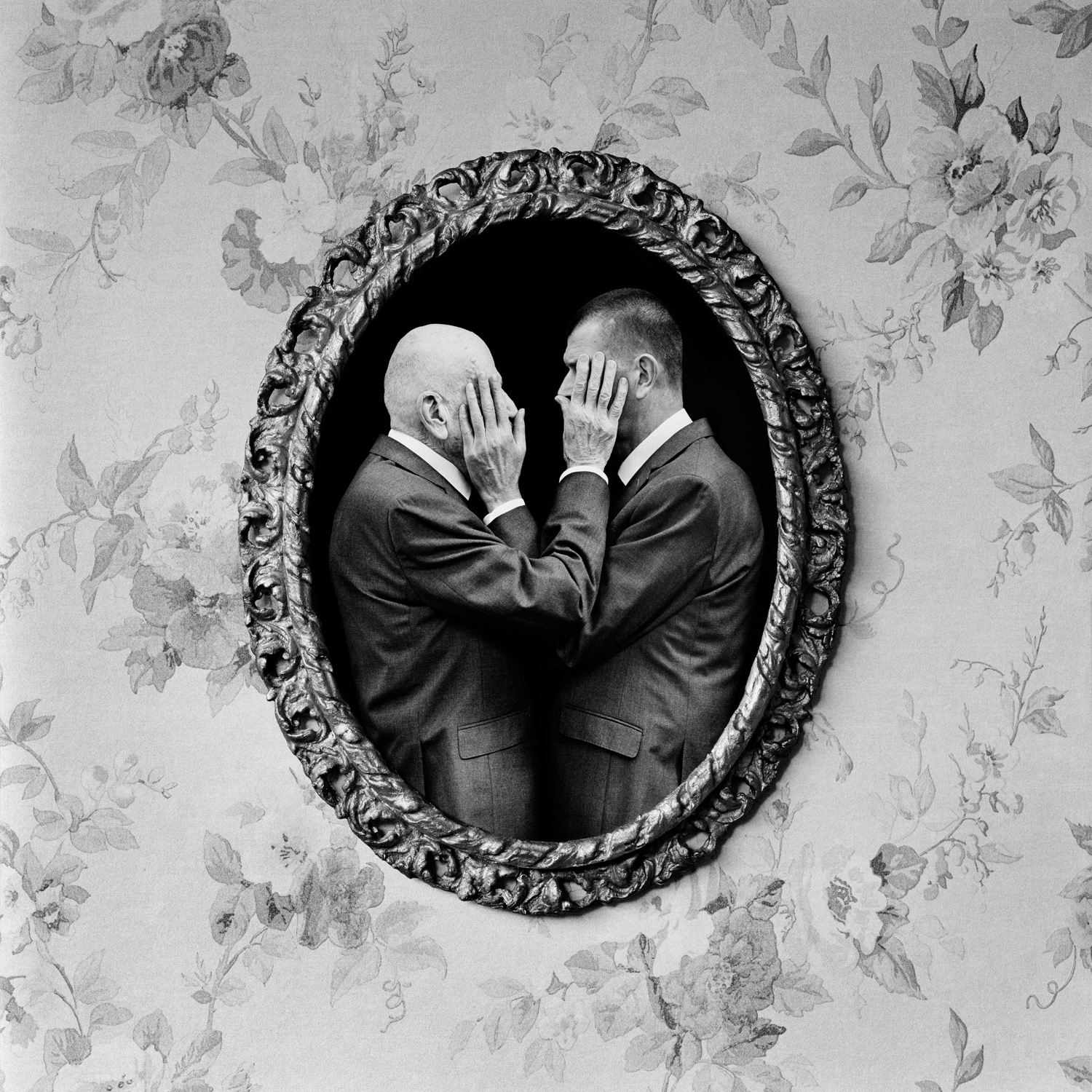

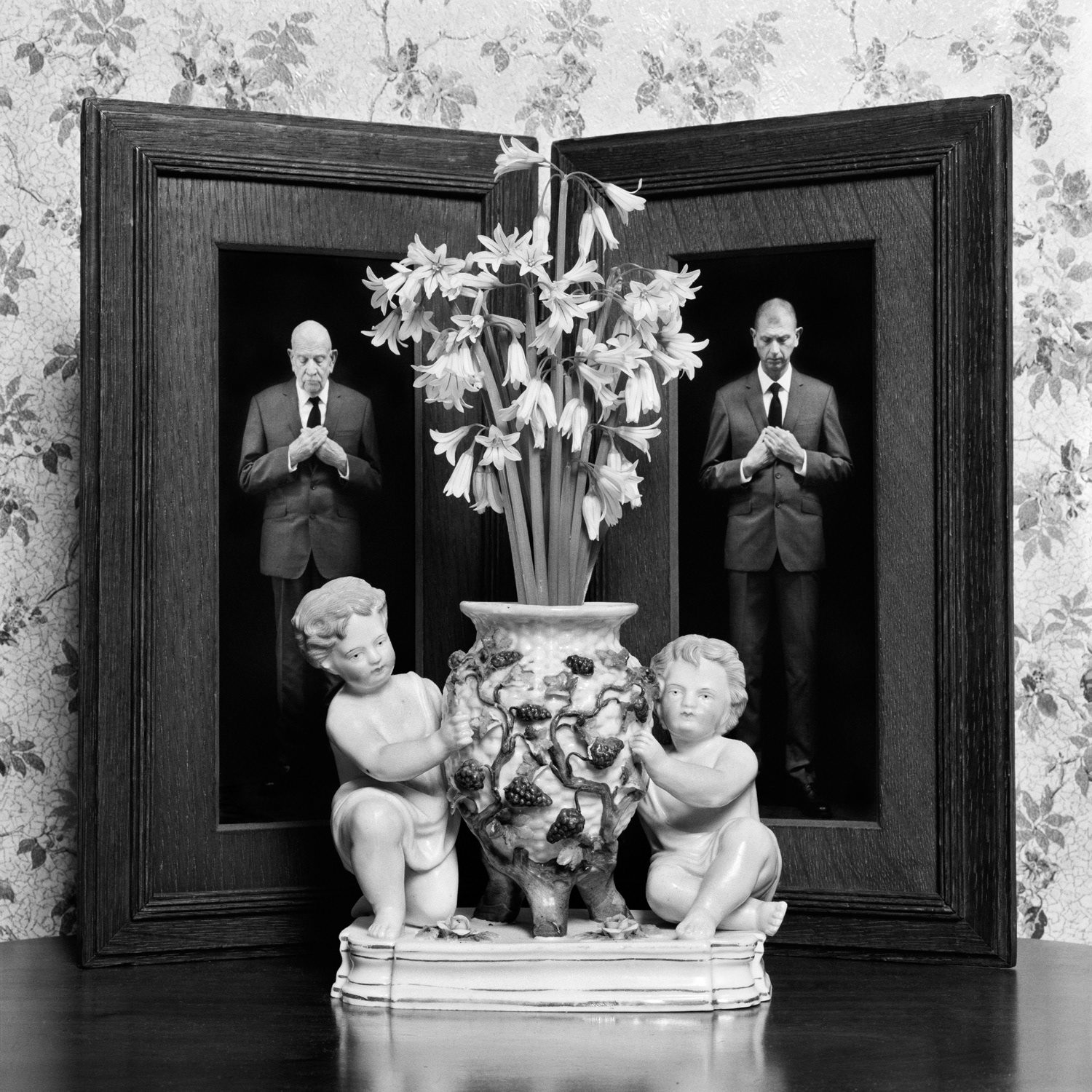

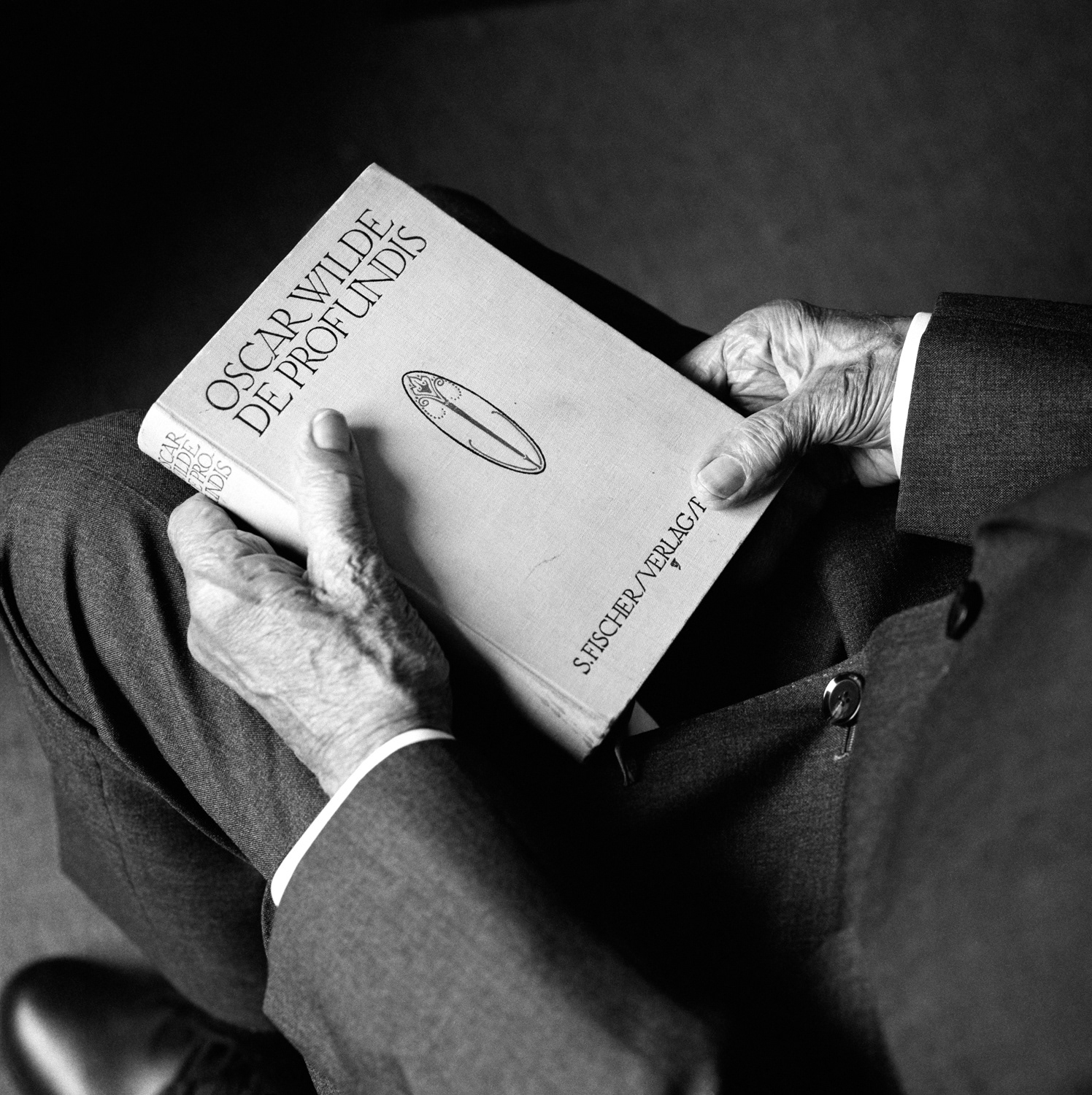

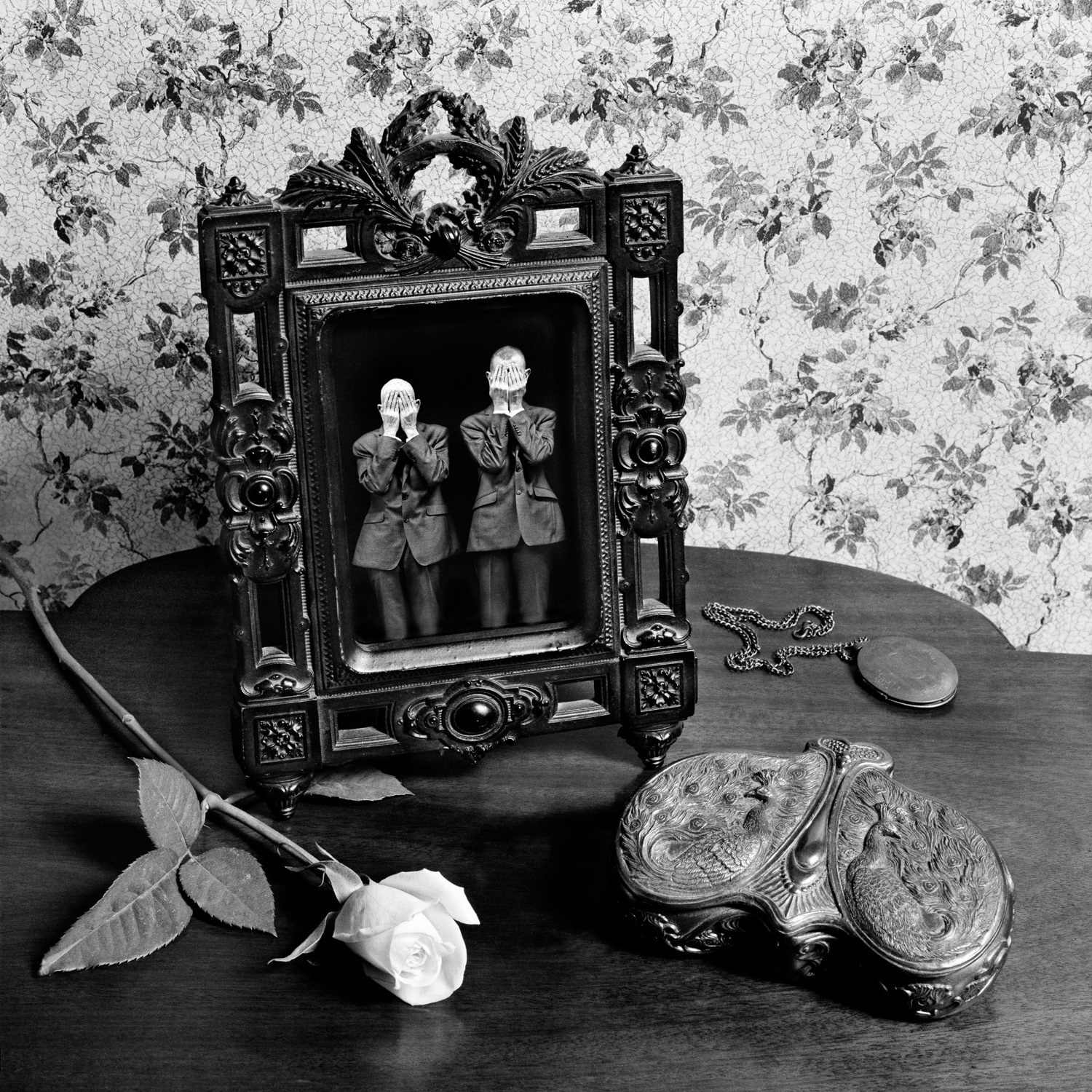

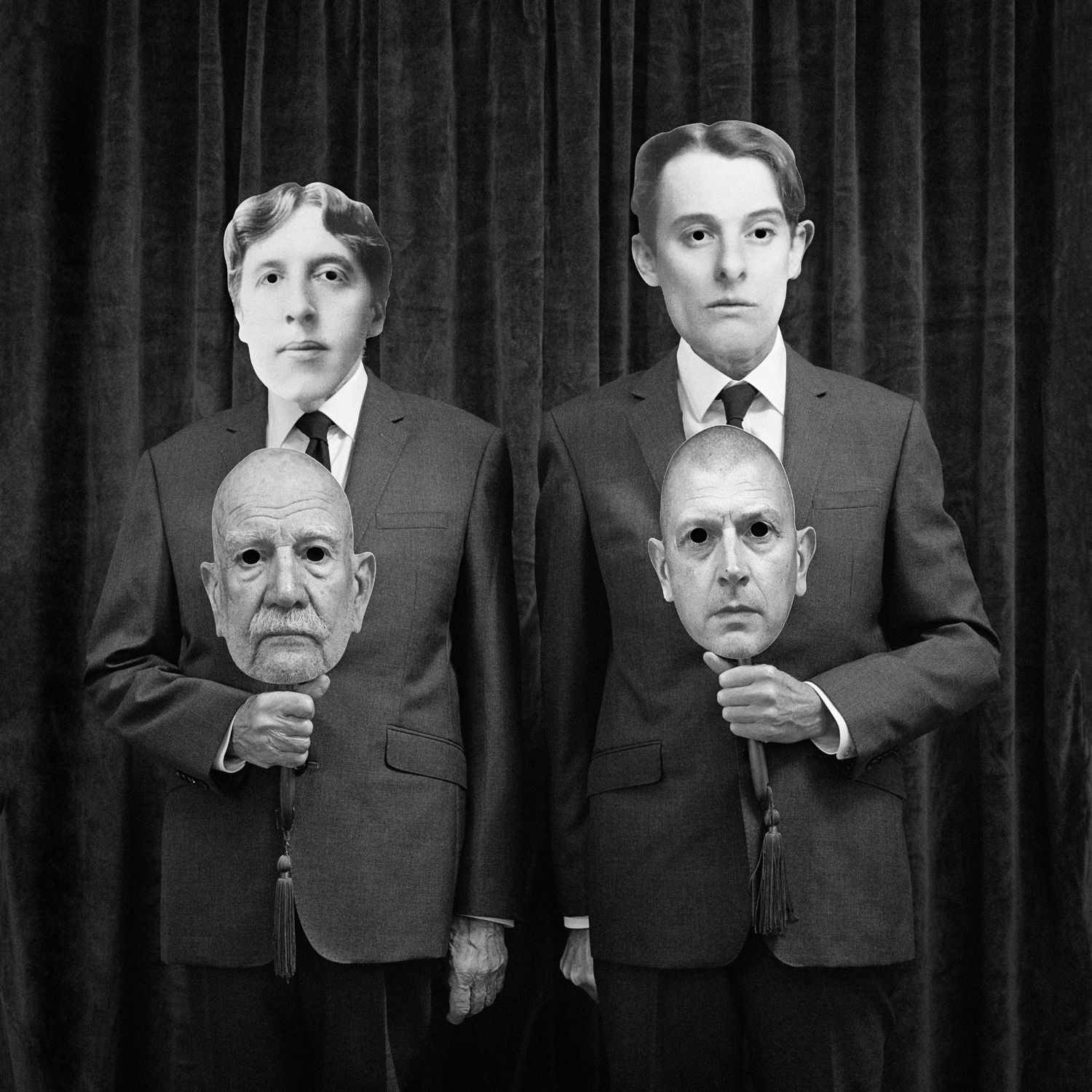

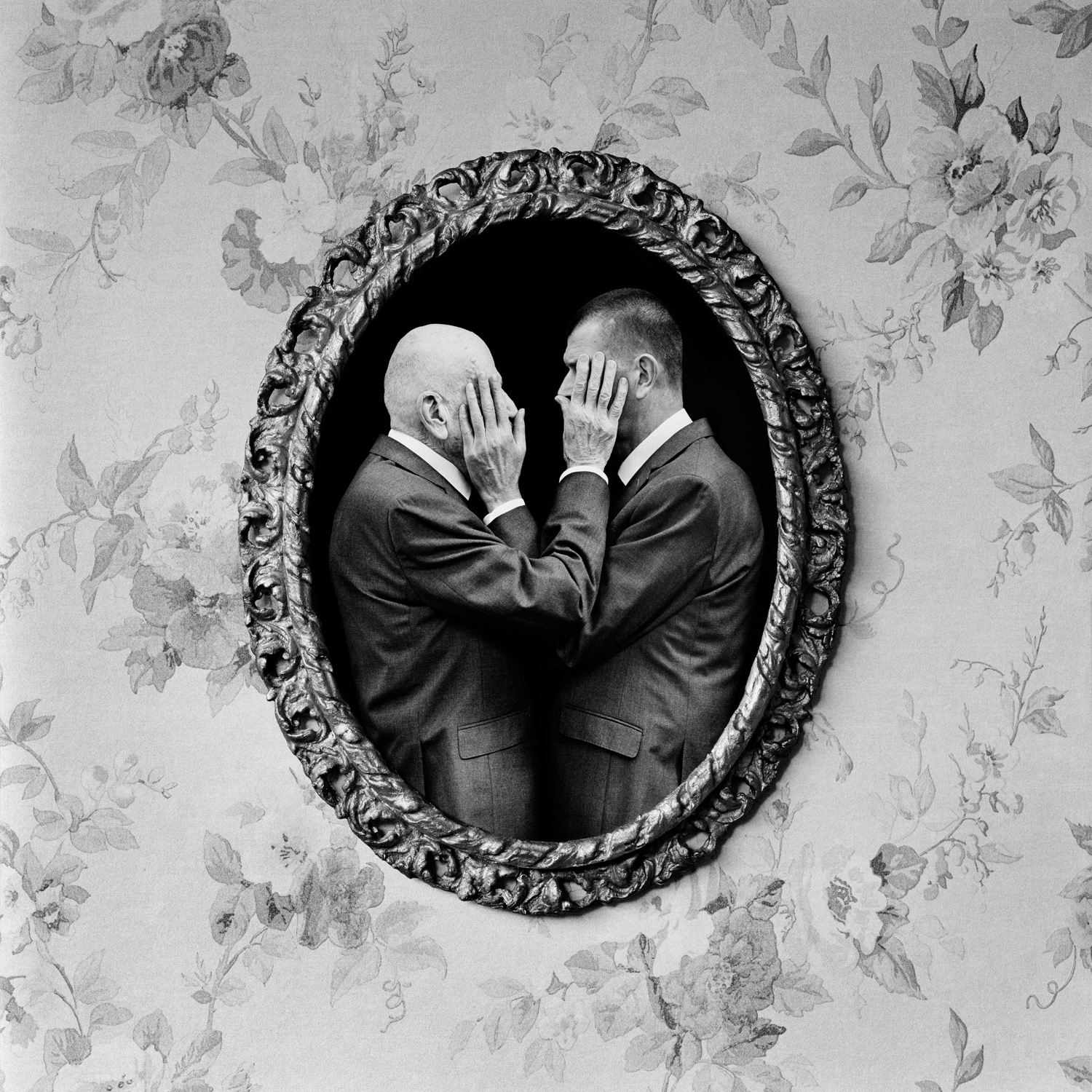

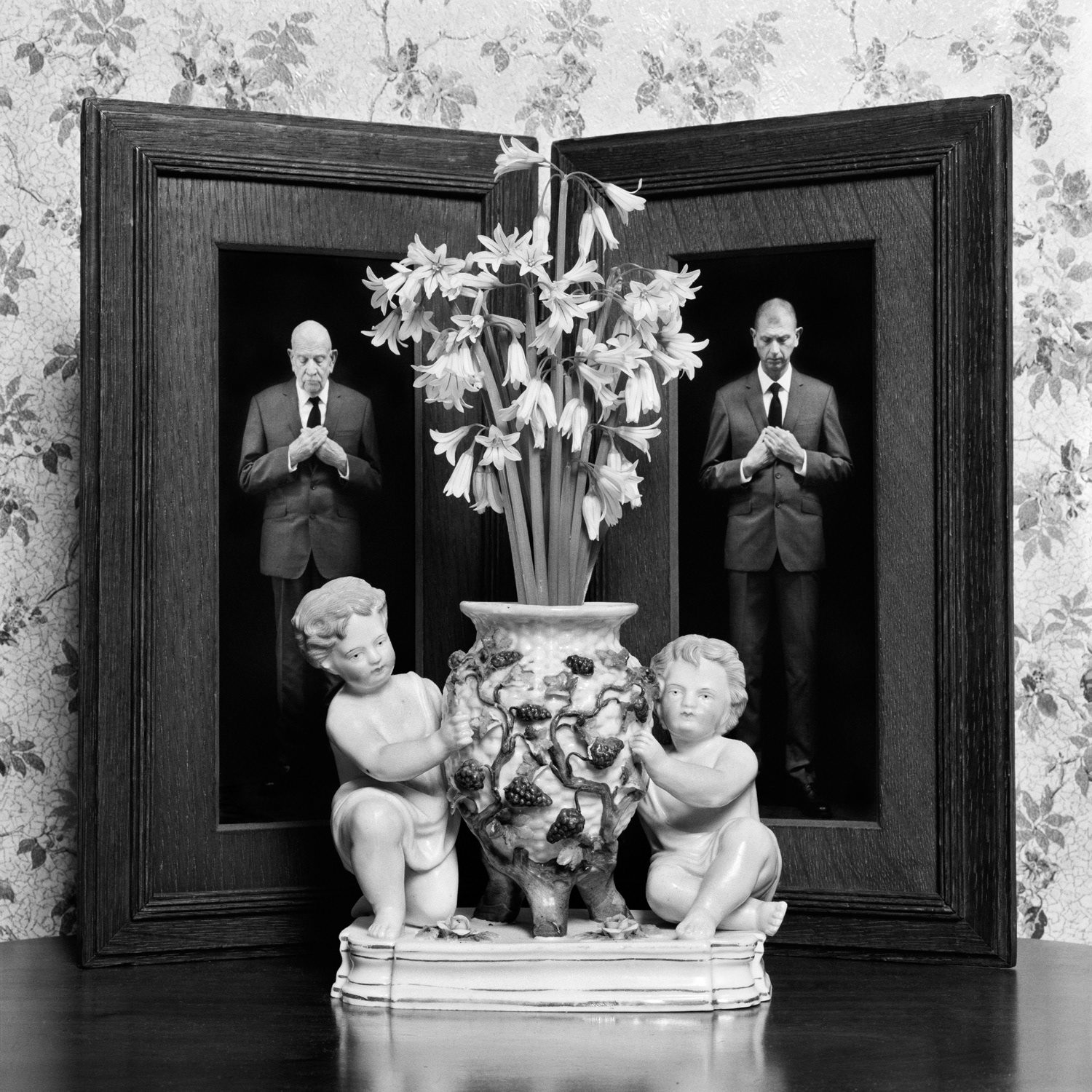

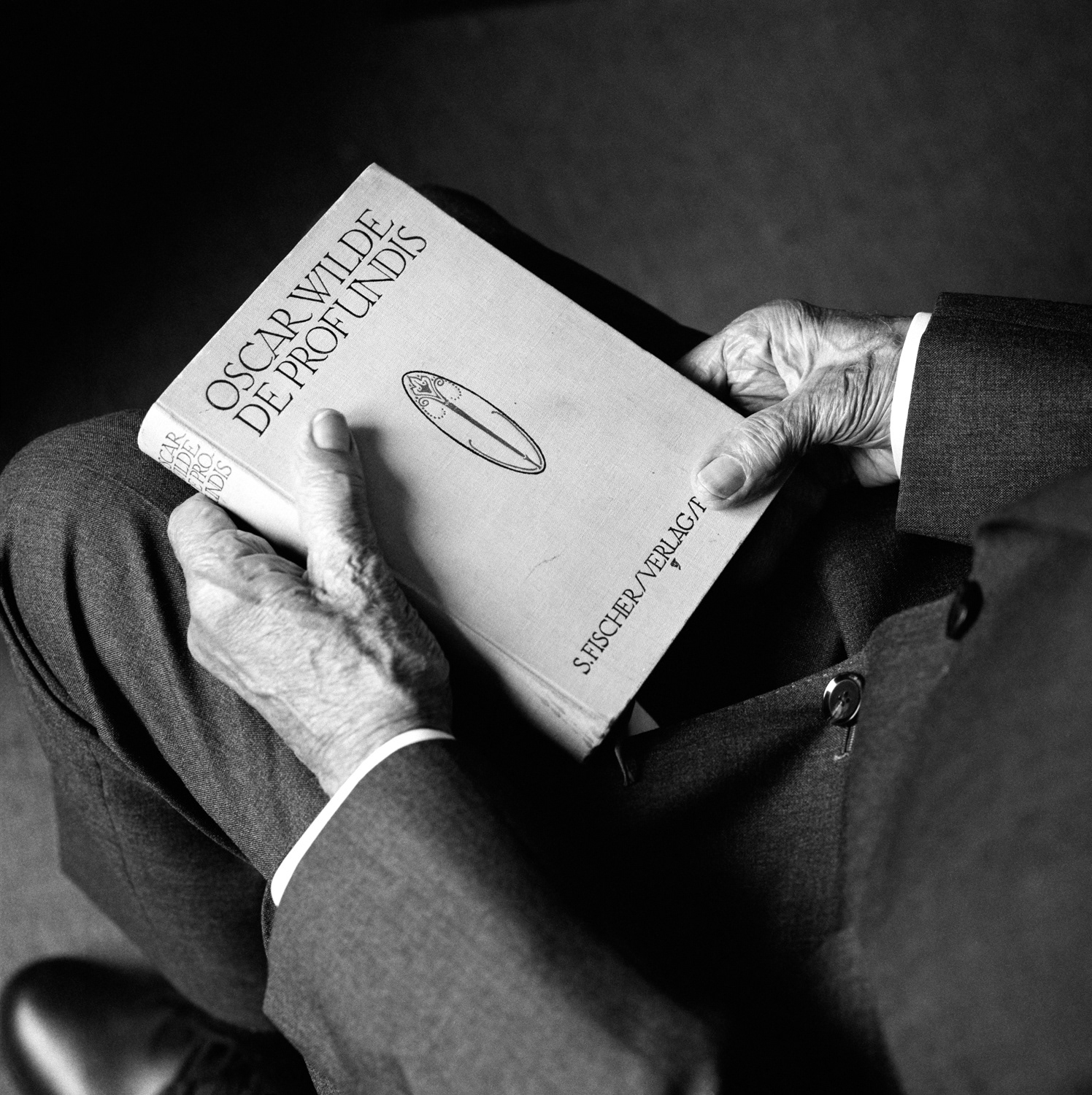

“Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth”. Oscar Wilde To imagine the world through the eyes of another is to free oneself of constraints, of the norms and conventions that bind us as a society. In Oscar Wilde’s case, these would be the Victorian values that would ultimately mark his downfall. Wilde’s reflection on the artist’s voice interpreted through another character could be viewed as analogous to the masking or closeting of his own desires in a period where one’s social persona and reputation could be ruined by the suggestion or slur of homosexuality. The flamboyant life as an aesthete provided a cover, to be hidden in plain sight, until he was exposed by the libel of sodomite, or what the Marquis of Queensbury collectively referred to as ‘snob queers’. More than a century on, while some things have greatly improved in attitudes to sexuality, being open about one’s sexual identity can, for some, be difficult to confront. My husband Peter and I perform ideas of queerness associated with our age and our working-class background. Peter grew up in a time where same sex love was against the law. I was 2 years old when the 1967 act to partially decriminalise homosexuality between men came into being in England and Wales. But a change in the law didn’t immediately lead to social acceptance. So, in adolescence, I learned to internalise and live a life of pretence. The staged tableau incorporate cliché, sentimentality, stereotypes, and transcoding. Collectively, these become a performance of belonging and otherness influenced by Freud’s description of uncanny in terms ‘heimlich/homely and unheimlich/unhomely’. Wilde’s novel the picture of Dorian Gray seemed prophetic of the fate that befell him. The mask of Dorian allowed Wilde to explore the hypocrisy of Victorian England. Dorian’s mask was the beauty of youth which remained untainted, while his portrait, his true self, festered in the attic- fuelled by desire and corruption. Wilde was often caricatured as a sunflower in the press and satirical publications of the day. The sunflower was the favoured symbol of the aesthetic movement, a group of fashionable figures in the art and literary world who pursued pleasure, sensuality and beauty for its own sake. To portray Oscar as a delicate flower was clearly intended to rob him of his masculinity and satirise him as effeminate. Homosexuals would often be mocked or parodied as delicate wallflowers or pansies. Peter and I adopt the head of a sunflower as an act of transcoding, to take what is used as a negative symbol to oppress and transform it into a mode of empowerment. The hybrid figures embody an alien-like presence and the upward facing open-palm pose of orans is a signifier of spirituality or ‘other-worldliness’. Oscar commented that the sunflower was akin to a gaudy lion which seems at odds with the limp wristed parody in the press. On release from Reading gaol, after his sentence for two years’ hard labour for gross indecency, Oscar would spend the last 3 years of his life in exile. His adopted countries were France and Italy. Paris would be his final resting place, memorialised by Epstein. France was a country more accepting of homosexuals than Britain in the nineteenth century.