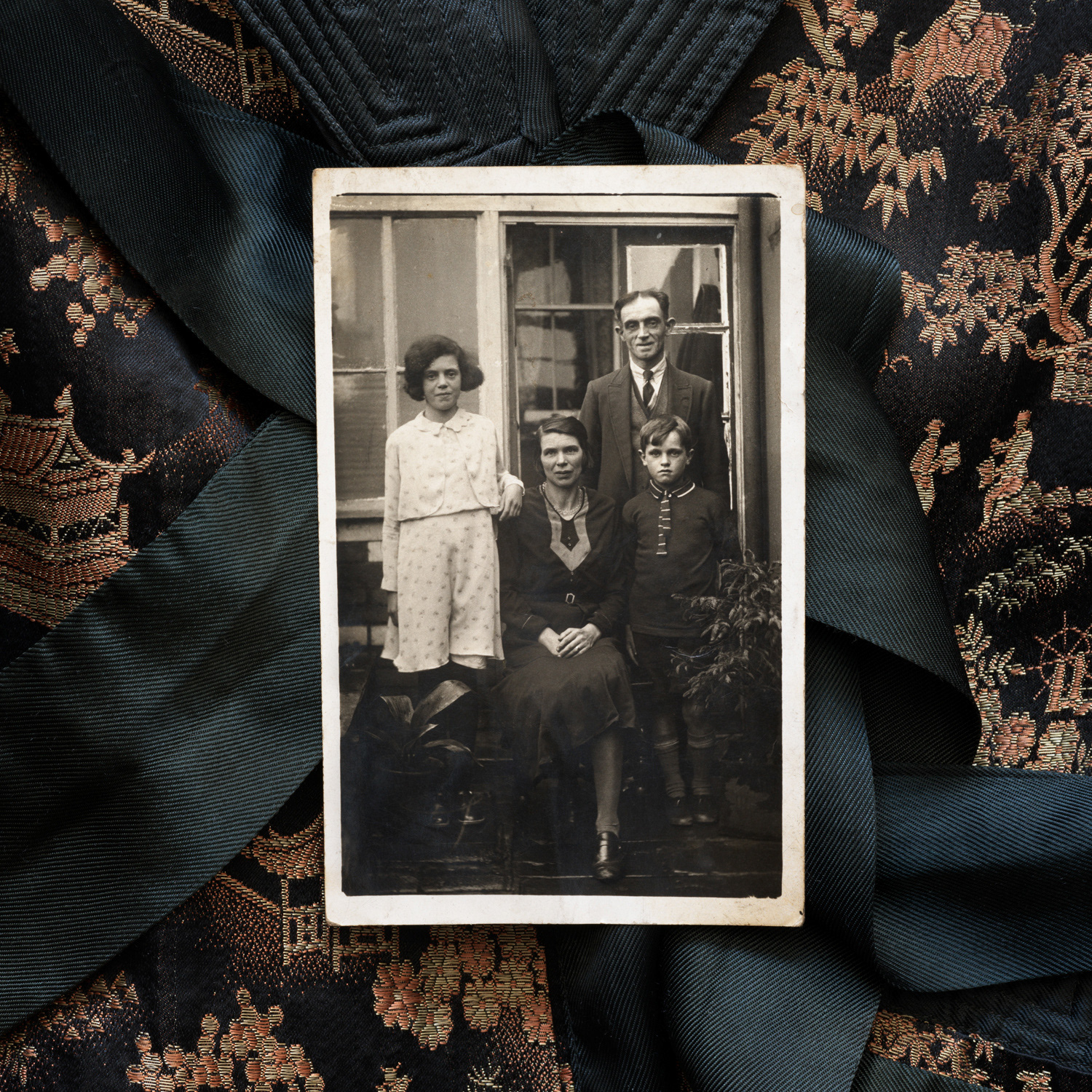

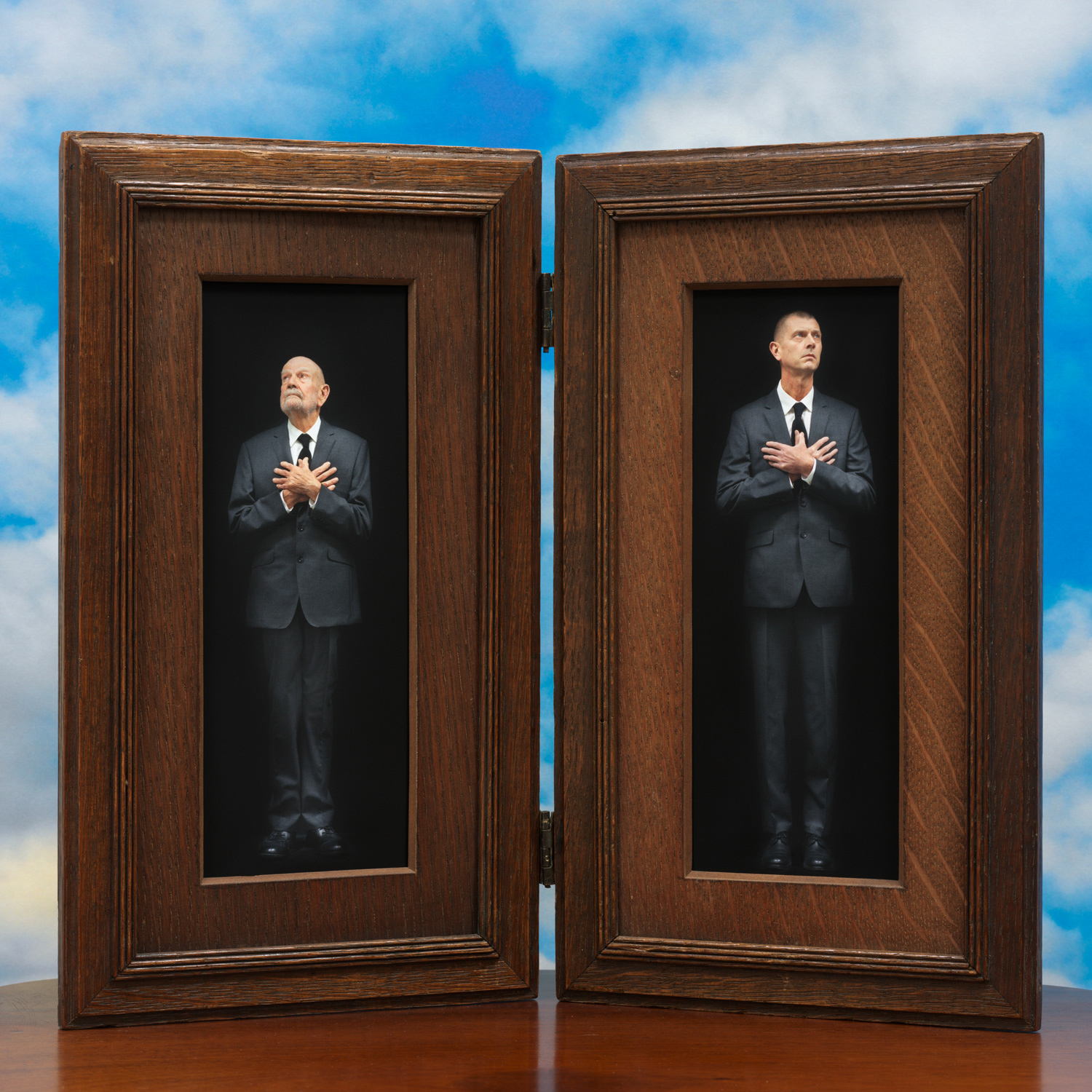

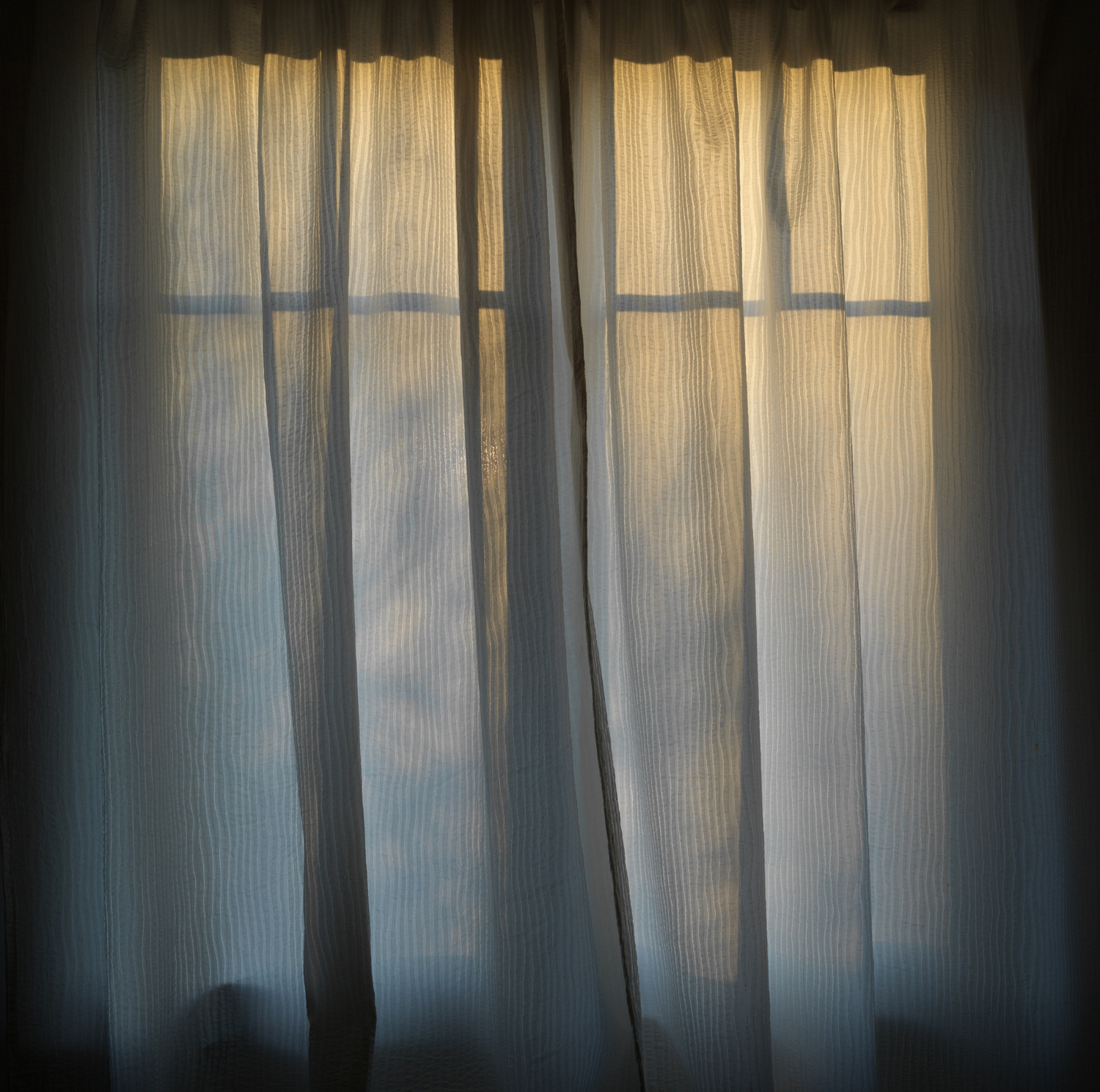

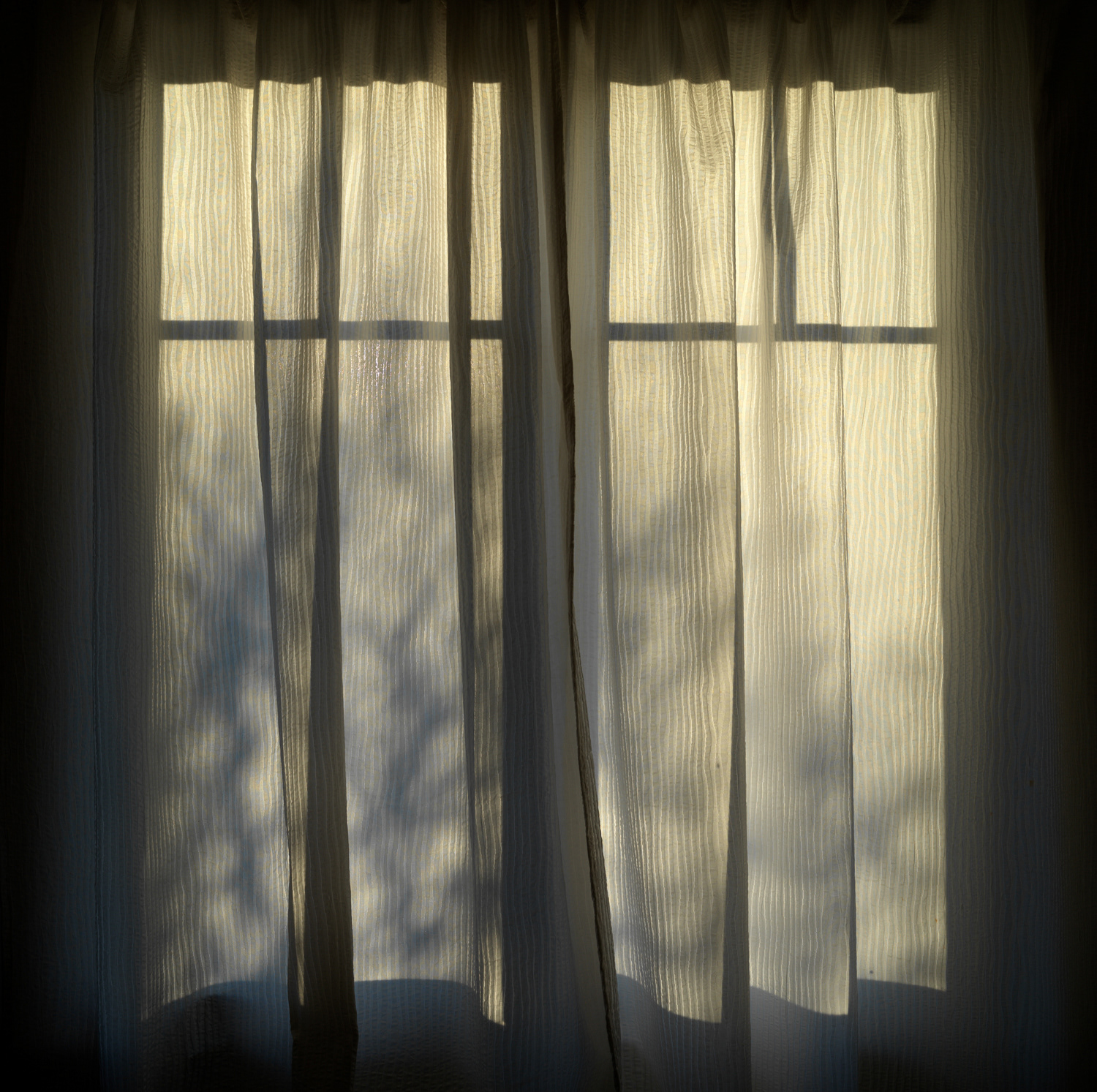

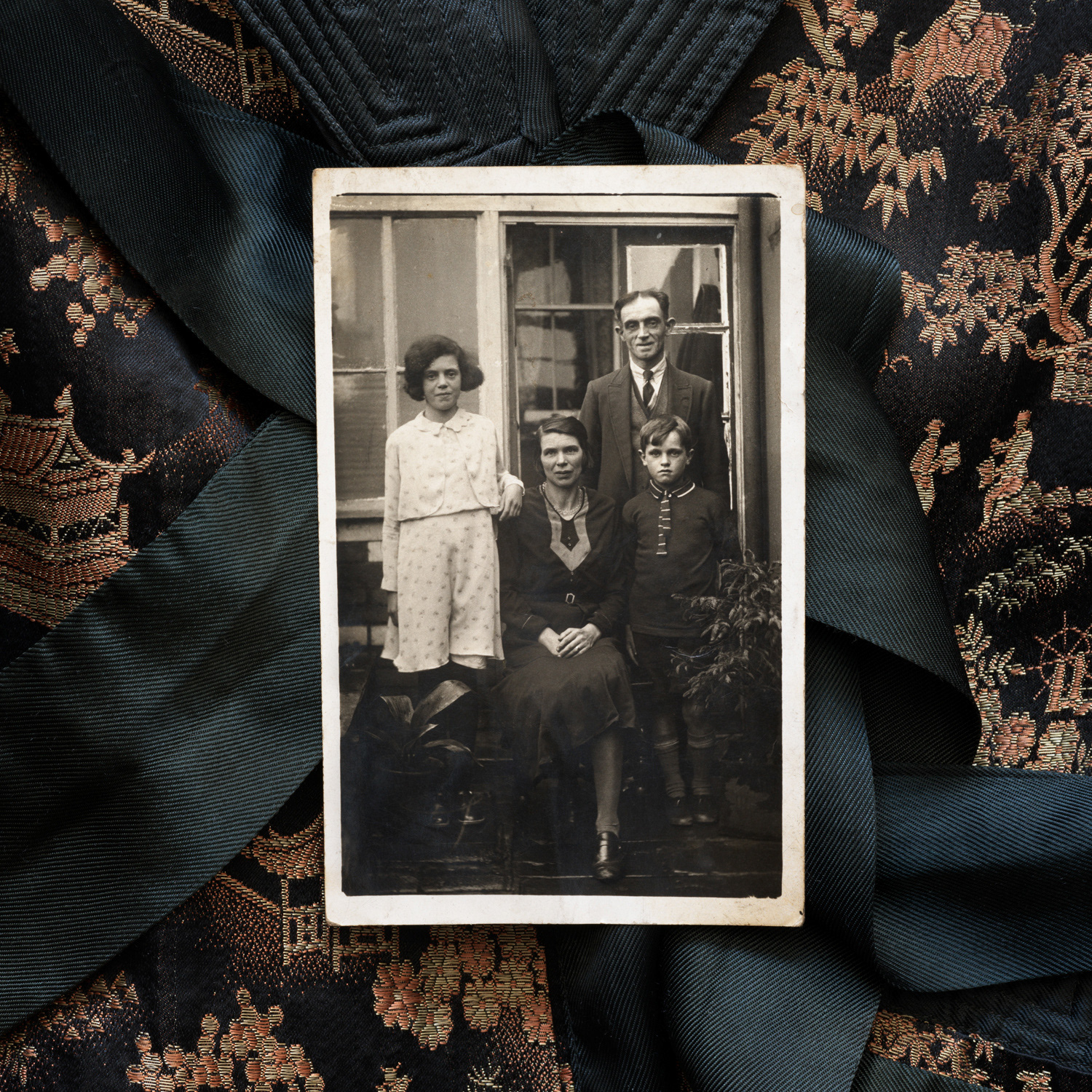

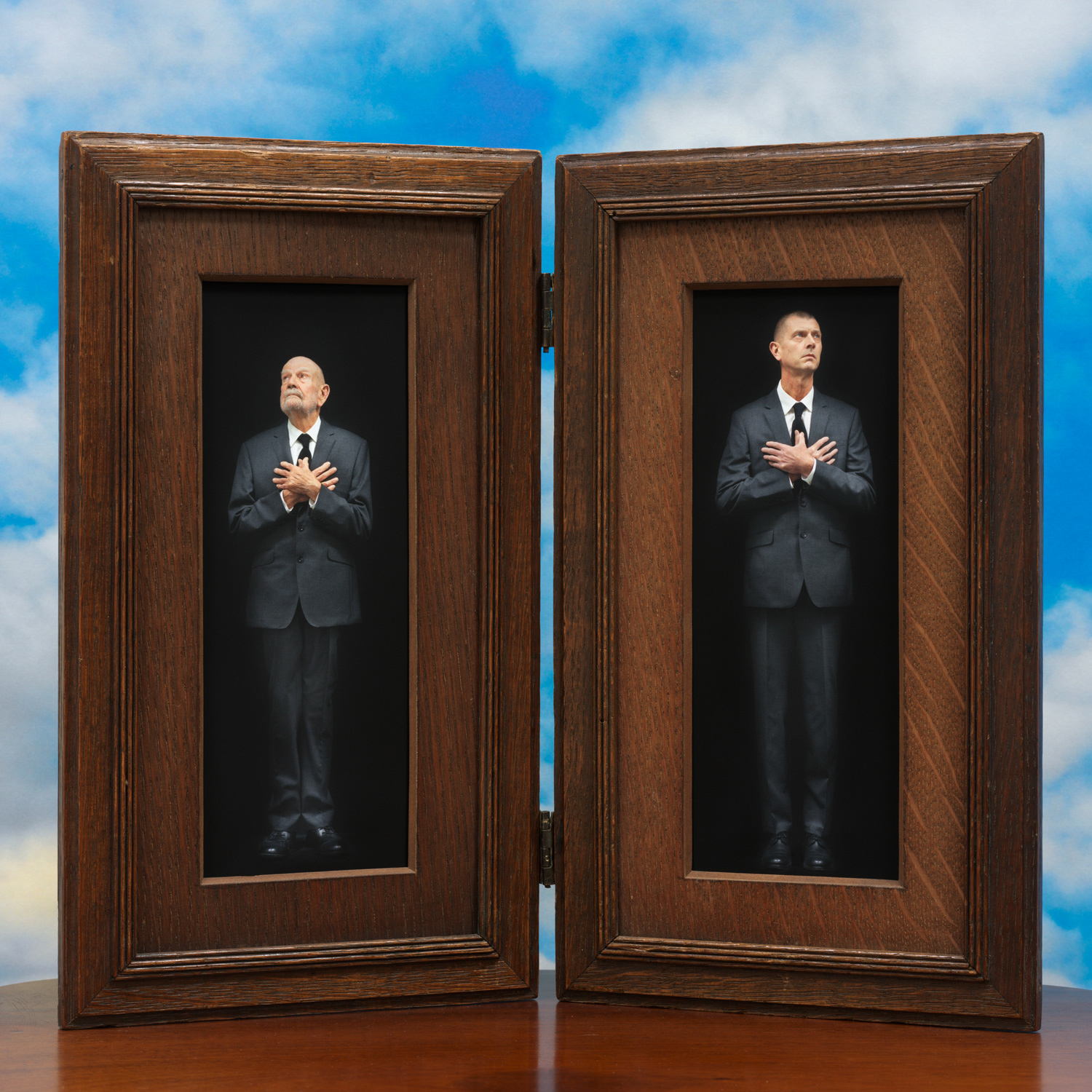

The decorative pottery known as ‘willow pattern’ tells the story of thwarted lovers. The tableau is thought to be based on a Japanese fable called ‘the green willow’, along with its Chinese variants. I remember as a child feeling upset when my paternal grandmother Elizabeth told me the story behind the willow pattern dinner service in her possession. Elizabeth was a doting grandmother and when I think of much of my early induction into society, it was channelled through her love and attention. The willow pattern tale of a couple who were killed because of their forbidden love seemed tragic to an infant who was not fully versed with the ways of the world. This fairy tale couple denied union through cultural and class prejudice seemed unjust and left a lasting impression more than 50 years later. Even at such a young age, when infants enact fairy tale fantasy, I was already aware that I would rather marry a prince than a princess, but I instinctively knew that I should keep such feelings to myself for fear of ridicule or ostracization. From my earliest memories I was aware that I was homosexual. These thoughts can be concealed in childhood, but when children enter adolescence, then talk of relationships amongst friends only emphasises ideas of otherness and often shame. In order to feel acceptance as a young gay man, I needed to eschew any sense of shame and, like the lovers in the willow pattern fable, I had to escape the world of my past to try and find belonging or even love in the future. Unbeknown to me at the time, this future would be with Peter, who I met as the 1980s drew to a close. It would have been unimaginable at the end of Margaret Thatcher’s reign that homosexual union would be recognised in law. The phrase coined by her government when introducing clause 28 was that same sex partnerships were nothing more than ‘pretend family relationships’. Peter grew up in a time where being homosexual was against the law in Britain. I never thought in my lifetime, or Peter’s for that matter, that homosexual union would gain legal standing. Fortunately, we live in a country where this has come to pass. Sometimes people do get the chance to live happily ever after. After leaving the village of my childhood I would not see my grandmother again. I’m not sure of Elizabeth’s precise birthdate, but I always thought of her as a Victorian. My father was born in 1922, so Elizabeth, or ‘Bess’ as she was known to family and friends, would have been born in the late Victorian or early Edwardian era. Her house on Queen Street certainly felt Victorian in its appearance and décor. The long corridors and dimly lit rooms furnished with heavy drapes, painted vases, Staffordshire figurines and lace antimacassars, embodied the previous century to a child in the 1960s. I particularly remember a glass vitrine which decorated the cast iron fireplace in a bedroom at the back of the house. The miniature scene within the dome represented a magical world that was beyond my reach, but one that I longed to step into, as if I were ‘Alice through the looking glass’. This window into another world is how I came to understand the feeling I experience when a photograph captivates me. I didn’t inherit anything from Elizabeth in terms of possessions or family heirlooms. I only have memories and one or two photographs. After my father died in the mid 1980s, I left the village of my childhood and feelings of guilt about his death and ‘coming out’ to my homosexual nature meant that I never returned to visit her in the years leading up to her death. I was told that she would ask after me regularly, but then as time went by, and it became clear to her that I wouldn’t be returning, she didn’t ask anymore. As I get older, I am more reminded of the woman who loved me unconditionally as a child. As a young man I didn’t believe that I would receive unconditional love as a queer adult. Whether that is true or due in part to the sense of shame one feels it’s impossible to know for sure, we can’t travel back in time to test the water. If one conceals a fundamental aspect of oneself, it’s follows that one will feel like an imposter or an outsider. These memories instil a sense of guilt for my own lack of empathy towards people who cared for me in my formative years.